Can A Worm Feel Love?

For some reason, we are debating the sentience, consciousness and emotions of worms and insects. Call it a thought exercise.

About this article:

Overview:

If worms, insects and other creepy crawlies can solve problems and feel pain, does that mean they can feel love? Probably not- because emotion, as humans know it, demands a kind of consciousness and contextual processing that bugs just don’t seem to have.

Tags:

Uncategorized

Topics:

Insect, Emotions, Feelings, Sentience, Consciousness, Cognition, Philosophy

Date:

Author(s):

Cain Parish

Can A Worm Feel Love?

‘Would you love me if I was a worm?’ – a common question from the bowels of social media and TikTok brainrot. The context has been covered elsewhere, but the trend was essentially a litmus test for the emotional literacy of men – could they understand that the emotional outcomes of projecting unconditional love to their very real human partner superseded the literal quandary of tolerating a relationship with a hypothetical worm?

Basically – could men read between the lines? Most failed. Some did not. Today, I am less interested in discussing this question, as it’s been done to death and I, for one, am uninterested to going to Bunnings for mulch on a regular basis. What is more of interest to me is the idea of the inverse – can a worm feel love? Or more broadly, can insects feel feelings at all?

Some prefaces. Yes, this is a weird and arbitrary topic to spend time discussing. Yes, I am aware worms are not insects. Yes, this introduction is a godawful segue. No, this is not likely to be the direction my career pivots towards, unless you mean overthinking largely ridiculous and unproductive topics, in which case I can and should be considered a leading expert.

So, if you’ve ever concerned yourself with if insects can feel, and what exactly that would mean – here we go. If you haven’t (which ought be all of you reading), read on anyway. I need the dwell time for my analytics.

Debating Difficult Definitions Definitively

It would be helpful to our thesis question to clearly map out what exactly we mean when we use particular words.

Can insects feel feelings?

To start with, I am entirely uninterested in the type of insect. For all intents and purposes, we’re looking at the philosophy of what it might mean to feel, crossed against the neuroscience that exists generally for beings with less higher-order brain function than humans. Ants, beetles, bees, praying mantises – all fair game.

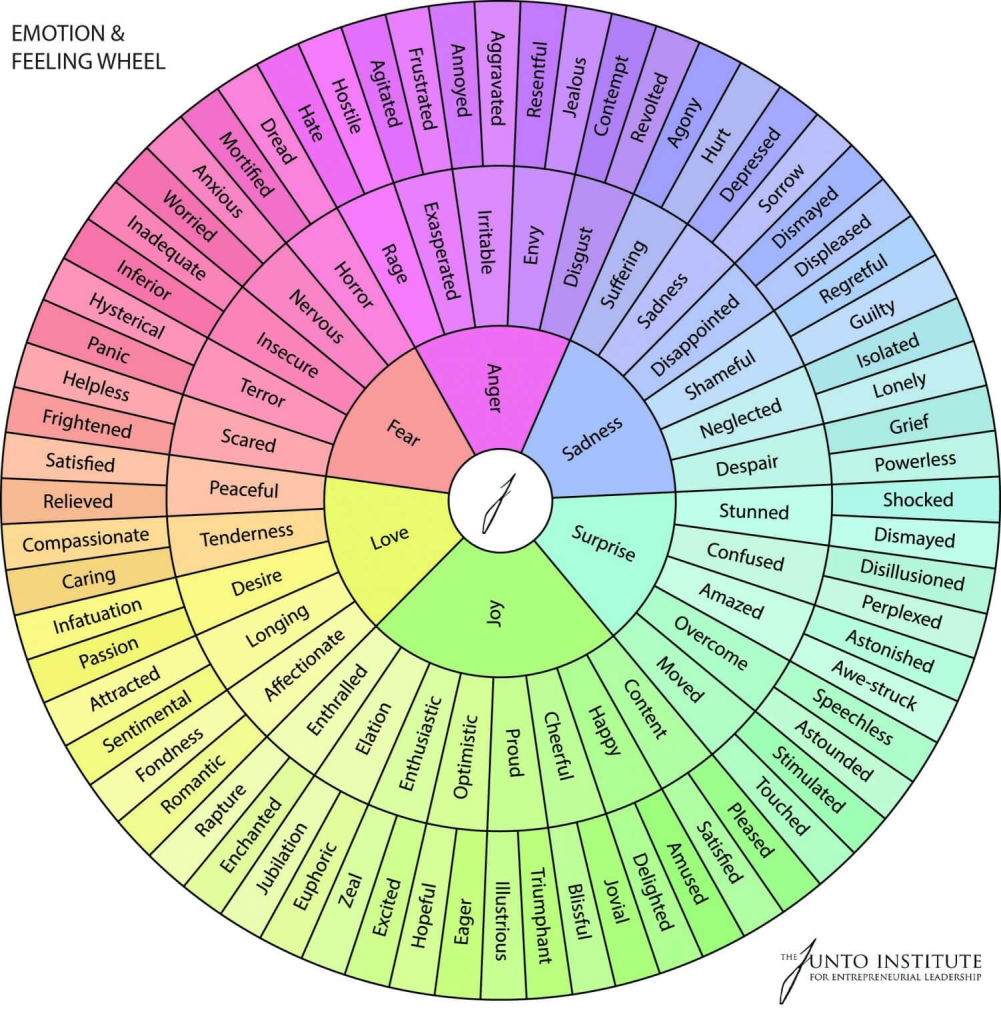

The more important definition is what it means to feel. For our purposes here today, I am referencing the idea of a human-like spectrum of emotions – anger, sadness, joy, excitement, surprise, etc etc. See the big ol’ wheel of emotions below – these are the types of sensations I am looking for an insect to experience as a human would.

By doing this, I am doing my best to avoid a handful of philosophical and semantic traps, namely the use of the word ‘feel’ as a relational verb rather than a holistic descriptor. It is relatively well-supported by science that insects can exhibit semi-complex cognitive behaviours and experience pain-like states. In this manner, insects could be considered to ‘feel’ pain, which is grammatically correct but does not cut to the heart of our issue, which is to beg the question of insects feeling joy or sadness explicitly.

The philosophy describing what feeling actually is and what it emerges from gets rather murky rather quickly. Depending on the neuroscience you subscribe to or the philosophical models you employ, there are a number of ways of explaining away a subjective experience of consciousness that would be required to feel emotions.

A working definition that we can use for our purposes is the following – an entity can be considered to have ‘felt’ an emotion if we believe it to have subjective, human-like consciousness AND it has the cognitive capacity to exhibit higher-order brain function that implies sentience and complex processing of non-literal concepts.

This is word salad, to be sure, and there is almost zero chance this definition holds up to philosophical or neurobiological scrutiny, but it works for our purposes. For starters, we must draw a line on what ‘consciousness’ does and doesn’t comprise. I am using colloquial definition and common sense. A living being is conscious, humans/animals/etc. A robot is not (AI people, send me emails and I’ll argue with you there). This is good enough for today – the hard problem of consciousness is avoided and the metaphysical musings of p-zombies and red rooms can be circumvented by just thinking like a normal person instead of a filthy philosopher.

Secondly, for a conscious thing to feel emotion, it requires cognitive capacity to move beyond impulse-based behaviour response. This is largely what separates humans from most animals, the grey matter required to understand things on a non-literal level and exhibit all the strange relational thinking that we do is no small feat. You can intuitively (again, using common sense to do our heavy lifting) understand this by trying to define ‘joy’ or a similar emotion. We cannot describe joy without relation to something else – it must be a reference to a non-literal state of mind and experience. When we are hungry, we are compelled to eat by acknowledging a biological drive. When we are joyous, we are overwhelmed with a subjective experience based on a reaction to something based in sense data that is given relational comparison to a neutral or non-joyous baseline. If you can forge a definition that works in practice that is any simpler and based on a lack of comparison, you are smarter than me and deserve a cookie.

Developmental psychology tends to back me up here – emotions are considered a subjective consciously felt internal experience that emerges for humans in response to specific situations (i.e. relational). In other words, good enough, but localised to our species. We gave name to feelings that we had – the feelings were emergent properties of our lives and communities. This will present issues for the poor insects, as we are about to see.

What Can Insects Do?

There are a number of studies that have looked at specific varieties of insects and their behaviour. The cognitive capacity from one species to another varies dramatically, and so implying that something which is true for a bee would be true for an ant would be folly. As we will see, this is largely irrelevant, so bear with me here.

Science has determined that particular species of insects have exhibited cognitive function. They have been noted as having brains capable of things such as learning, navigation, communication, basic problem-solving and very simple forms of metacognition, among other things. This is interesting for our purposes – they are not merely impulse driven as we would assume a dumb, simple-minded creature to be.

This would satisfy at least one of our conditions – the idea of the grey matter required to have complex subjective experiences. The concepts above imply that there is a good portion of relational cognition occurring – complex pathfinding and problem solving, for example, would show that insects can think.

So we have a conscious entity set that can think in complex ways. What’s the issue then? It would be simple to imply that if insects can think, they ought be able to feel.

Unfortunately, this is where science halts – there is no experiment that would determine if an insect can feel, because emergent emotional experiences are subjective, and based entirely on our own language and sense data. Our human emotions would likely not comport onto the lived experience of a bee, for example. Just as different cultures and languages describe circumstances and emotions in different ways, using words that are alien or un-translatable to other societies, it would be impossible to determine if an insect experiences things in the same contextualised manner that we do.

So Is That It?

In short, yes. To say that something non-human is feeling is to appropriate their own lived experiences with our own models of emotion and description.

This is the frontier that can likely not be solved without a form of communication that transcends the language barrier between species. Even if we prove that insects satisfy the definition of sentience (a dubious and debated concept in both science and philosophy) and have the cognition required to exhibit contextual emotion (not out of the question but likely improbable), we cannot give insect-based context to the experiences of insects because we simply lack the means to do so.

As is evident from the above, even the gentlest and most generous definitions of emotions and consciousness cannot bridge that gap – just because a bee can feel pain or solve problems does not in any way support the idea that they’d feel sad about being in pain or feel accomplishment at solving a challenging issue.

The behaviour of insects indicates cognitive processing in various forms. Whether you are convinced or unconvinced by the logic I have outlined here is largely down to your beliefs on the philosophy of mind that would define and explain emotions. Unfortunately, as I have described in the above, science remains unconvinced that emotions exist even in the smartest of creatures – they lack the subjective human sentience required. It is my contention that the philosophy broadly agrees with the science. It would be a stretch to loop the definitions of feeling to include insects, and I for one am okay with that.

Thus, we have our answer. No matter your feelings toward your own worm-girlfriend, they are just like my ex – incapable of loving you back.

Stay informed

Receive updates on new research, book releases and insights into strategic communication and personal culture.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime. Your information is never shared.