How To Do The Most With Words – A Guide To Selective Synonyms

Selective synonymy is the process by which we select and use one word over another. Learn about how context and connotation inform our language.

About this article:

Overview:

Selective synonyms refer to words that appear nearly identical in meaning yet carry subtle stylistic distinctions that change the way we phrase our communication. Both literal and non-literal communication can be affected through intentional word choice – grounded in linguistic principles such as illocutionary intent and perlocutionary effect – tailored to suit practical aims or aesthetic preferences.

Tags:

Uncategorized

Topics:

Linguistics, Synonyms, Communication, Speech, Language

Date:

Author(s):

Cain Parish

What are Selective Synonyms?

What is the difference between the following phrases?

“This elephant is big.”

“This elephant is large.”

Literally speaking, the difference is a single word. The words ‘big’ and ‘large’ mean the same thing – these are synonyms that serve identical functions for the purposes of communicating that the elephant in question is a sizeable creature.

When we think about synonyms in this way – i.e. words that mean the same thing but have different stylistic or aesthetic applications – we refer to this as stylistic synonymy.

This is because the meaning of the sentence, the semantics of the content and the thing the sentence means to communicate is preserved in both options. The choice comes down to nuanced factors and subjective preferences – i.e. ‘style’.

In more formal linguistic terms, our illocutionary intent (the intention of our sentence’s communication) stays the same, but our locution (the content of the sentence) changes. So the question becomes – what factors influence our choice of stylistic synonyms, and how can we use this phenomenon to our benefit?

Context of Selective Synonymy

If we continue with our initial example, by tossing away the rest of the sentence, we can focus on the single distinction – using the word ‘big’ instead of ‘large’ or vice versa. How do we make such choices in everyday life?

Intuitively, we may all find that we draw some subjective inferences from either word. For example, picture a person saying the word ‘big’ in a sentence. What kind of person are they? What is the rest of their vocabulary like? What impression do they give off and how are they likely to communicate?

This is the intuitive act of understanding connotation – the small individual biases and sentimental attachments to particular words. If it helps, imagine this process as the act of selecting a baby name. The name ‘Rick’ might have no meaning or a positive meaning to you, but a horrible meaning to your partner – who was egregiously bullied by a Rick in high school.

In this case, the same term has two different sets of meaning to two different people, owing to personal experiences, backgrounds and emotional reactions. In actual fact, every single word in each language experiences the same phenomenon – we have connotations to each word in each sentence we come across.

If we wish to be more effective or persuasive with our language, or to find ourselves better fitting in with a particular demographic, we can use these connotations to our benefit – by picking and choosing words that best suit our practical purposes, rather than our aesthetic dispositions.

Selective synonymy is the process of actively choosing one word over another for the practical benefit of the respective connotation. In our elephant example, you might understand the word ‘large’ to sound more formal or have a higher perception of intelligence attached to it. In a situation where you want to impress someone – the word ‘large’ might then be more applicable.

An Example of Selective Synonymy

We can then think of each fragment (or even each word, in extreme cases) in a sentence to be a sequence of selective synonyms that we’ve chosen to best accomplish our illocution – our intentions behind our sentence – in the context we’re uttering the sentence.

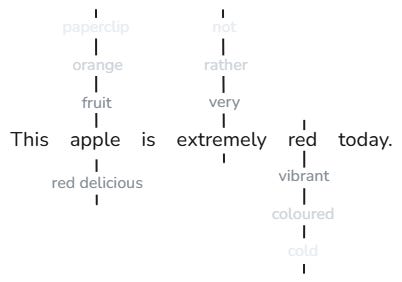

This might be challenging to think about, so let’s use an example: “This apple is extremely red today.”

You can think of each part of this sentence as a set of choices, each of which either supports or detracts from the intention of the sentence – to convey that the apple appears red-coloured, significantly so, specifically the same day as we’ve expressed this sentence.

Think about some options for words we can change out – what would we convey if the word ‘apple’ was exchanged with ‘orange’? Our sentence would take on a different meaning, and if there was indeed an apple in front of us rather than an orange, the new meaning would be counter-productive to our intention.

This binary choice can be applied to every single word pairing in a sentence, and owing to the (very hotly contested in linguistic philosophy) fact that language cannot contain perfectly exact synonyms, every pairing can be found to have one option that better contributes to the sentence’s goal than the other.

So our sentences start to look like the following:

Where each portion of our sentence can be swapped with synonyms or other words of a similar grammatical purpose to create all manner of effects on the listener.

For professional writers, speakers and those concerned with academic or very strict literature, their sentences are constructed exactly this methodically and intentionally. It can seem overkill or too intensive to think of language in this way, but our communication gives us exactly what we put in – our effort is rewarded in our interpersonal interactions.

So, How Do We Know What Word to Use?

Once we have established our utterances to be compositions, sets of choices of words to achieve a goal, we need to find a way of understanding what word choices will help or hinder us.

This is where our puny human brains start to break down – the amount of information we’d need to be able to take in, process and analyse in order to make a determination with a high degree of certainty is very much outside the realm of human capabilities.

There is certainly a difference between knowing that our choices have an impact in theory, and being able to determine distinctions in some of the harder choices in practice. This difficulty is compounded when speaking or holding a conversation, as we no longer have the luxury of time – our snap decisions have to be as closely aligned with our goals as possible, else we risk miscommunication or poorly effective speech.

Thankfully, just because it is impossible to be a completely deterministic robot doesn’t mean we can’t get better at the skill of selective synonymy. If you think about it, we are able to get very, very effective results by just keeping some broad principles in mind.

Some Broad Principles for Selective Synonymy

Let’s assume our goal is to convey exactly what we’re saying – whilst subtext is a massive part of human communication, complicating our explanations of these principles by making allowances or explaining nuances of non-literal communication is going to keep us here all day.

Let us then borrow from our above example – there truly is a red apple in front of us, it is notably red today, for some reason, compared to other days, and we’d like to convey this information to another person to make them aware of this fact.

We can eliminate countless options from our selective synonym process with the following principles:

- The more explicitly specific, the better, because specificity reduces the risk of ambiguity, a contributor to miscommunication.

- If a literal term exists for something, the better, as this is the most specific option we have available.

- We should try to provide relevant context where it is necessary. For example, if the apple is notably red today, compared to the vibrancy of its colour yesterday, and it is likely to return to the previous shade tomorrow, it is helpful to communicate the relevance of this time window.

- If an adjective provides helpful context, include it. In this instance, there isn’t much difference between the words ‘very’ or ‘extremely’, so either option works, but in some cases, it can be wise to pick specific adjectives for their connotations or particular meaning. For example, the word ‘proficient’ can be more specifically or contextually applicable than just ‘good at’, ‘knowledgeable’ or ‘talented’ – we should always strive to pick the most context-appropriate option.

- We can use referential words to specify the apple in question – there is an obvious difference between ‘This apple is red’ and ‘Those apple(s) are red’.

You’ll find that 99% of the possible words that we have the option of can be eliminated with these principles. Much of practical communication can be simplified down to maximising our specificity – miscommunication is the enemy of communication, and specificity is the antidote to miscommunication.

When we do start to explore the possibilities that subtext and non-literal or non-explicit communication can offer us, it is worth doing so with the understanding that specific literal communication is the default – the baseline. When learning a second language, it is this form of very unsubtle communication that we begin with, as it is the foundation on which transmission of information is built.

Much of our ability to create interesting results with language comes from the interplay between literal interpretation, and subjective meaning-between-the-lines. Whole types of communicative practice come from the intentional straddling of the literal versus the non-literal – a simple example being sarcasm.

To explain sarcasm, we would say something like “A type of humour created by someone saying something that simply -isn’t.-, as if it -is-“, an explanation that makes no sense until you hear someone being sarcastic, at which point you understand the formula perfectly. It is the act of weaving between what is said explicitly and what is understood below the surface that makes sarcasm and other forms of communication possible.

You may naturally find yourself wondering; “How do we choose our words in those cases? It’s all well and good if we’re doing literal communication – just be as specific as possible – but what metrics can I use when I’m not being 100% literal?” Excellent question, dear reader. Let’s look into that.

Non-Literal Selective Synonymy

The short answer to the above? Nobody truly knows, and we lack the facilities to be able to find out. Cool, article over. Everyone head home.

If that’s not particularly satisfying, let me explain myself somewhat. As we mentioned before, it is outside the scope of human limits to assess all the factors that contribute to a deterministic view of human social situations. We can be the best communicators humanly possible and there is still totally room for misunderstandings and circumstances that we are unable to predict or understand – mainly because of a single confounding factor; the other person.

We can take the most intimate care of our own selective synonyms, but if the other person’s brain doesn’t work in a collaborative manner with ours, things can still go wrong. It takes two to tango.

The resultant outcomes of our communication on the receiver is called the perlocution or perlocutionary act, and make no mistake, as much as we can strive for better outcomes with our speech, the perlocution of our sentences is outside our control. The reception of our utterances rests squarely on the receiver themselves – we can certainly increase the odds of a favourable reaction, but it is still an act of gambling.

Technically this applies to literal communication as well – but in practice, it tends to be much easier to strive for perfection when our only metric is to capture the semantic nuance of the literal. This is the domain we actional communicators work within – the practical.

Practical Non-Literal Selective Synonymy

So, if we abandon the idea that we’ll ever be perfect subtextual communicating machines, what are we aiming for? Put simply, pattern recognition. The human mind is extremely efficient at understanding and extrapolating on patterns, sometimes to our own detriment. Gambling is as widespread an affliction as it is because of the human tendency to see patterns – the chaotic nature of chance games is a tempting canvas to try and apply order to.

We can attempt to make order from the chaos of other people in a similar way – but as with gambling, we will often make inaccurate assessments about a random universe, and get burnt as a consequence. Thankfully, unlike gambling, it is not a given that the house will always win.

So, here goes. To make choices about selective synonyms in non-literal communication, we need to use patterns built up from experience and understanding about both communication as a whole, as well as the recipient(s) of our utterances. These patterns are expressed as perlocutionary metrics, or the spectrums along which non-literal communication can be determined to be effective at achieving the intent of the utterance.

Vague? Yes. Does it need to be? Absolutely. Even trying to understand the wide variety of intentions that we place behind our speech is a task that boggles the mind. Thankfully, smarter people than I have done some of that work for us. Linguistic philosophers describe illocution – the intentions/objectives behind our utterances – as belonging to one (or more) of five categories.

- Assertives: Utterances that commit the speaker to the truth of a proposition, such as stating, affirming, or describing (e.g., “The sky is blue”).

- Directives: Utterances intended to get the listener to do something, such as requesting, ordering, or advising (e.g., “Close the window”).

- Commissives: Utterances that commit the speaker to some future action, such as promising or offering (e.g., “I’ll help you move tomorrow”).

- Expressives: Utterances that express the speaker’s emotions or psychological states, such as apologizing, congratulating, or thanking (e.g., “I’m sorry for being late”).

- Declarations: Utterances that bring about a change in the external situation by virtue of being spoken, such as resigning, declaring, or baptizing (e.g., “I hereby resign”).

So, in this context, our apple-based example from earlier could be considered a literal assertive utterance, if we fancy getting technical with our labels.

As a non-literal example, consider a passive aggressive expressive (what a mouthful) – “Nice of you to finally make it…” – where the literal intent could be interpreted as expressing joy at a person arriving at an event. As we all know from dealing with passive aggression, however, the real intent is often the opposite – to deride someone for being late, to express displeasure, or to produce guilt and shame in the receiver.

More to the point, each of these categories have different perlocutionary metrics – different priorities and differing views on what success looks like.

Following on from our non-literal example – how would we be able to know if we did make someone feel guilty for just arriving at our event? Or, more accurately, what variables would we look to in order to determine what selective synonym options would cause the most guilt?

Intuitively, we can look to things like the receiver’s emotional suggestiveness, their preference for maintaining social norms, how considerate they are of being polite, etc. These are our perlocutionary metrics, and they can be most accurately determined the more intimately you are able to know and understand the receivers of your utterances.

*As a side note, this is why family can often be so talented at these non-literal forms of communication – they have the most time and exposure with you, so they are best able to identify these variables and best able to engage in selective synonymy to utilise this information about you.*

Perlocutionary Metrics

Bluntly speaking, the nuances of every possible or relevant perlocutionary metric could fill an entire book. What is easier than determining an entire framework is providing a system by which you can develop your own.

The question ‘Why?’ is all-powerful for determining your most relevant perlocutionary metrics. If you can semi-accurately determine the ‘Why’ behind someone’s motivations or their psychology, you will likely find the most useful metrics not to be far behind.

This is a challenging task in itself, and is something we typically reserve for the realm of psychology – but again, we don’t have to be perfect, simply practical. Guess and check – if we can think of a reasonable explanation or motivating desire that guides the other person to their stance in our conversation, we can make an estimate of some potential perlocutionary metrics, try them out and see how we go.

For example, say we’re looking to subtly find out when our friend’s birthday is so that we can organise a surprise party without them getting suspicious. What do we know? Here’s a list.

- We know that they have to be unaware of the relevance of their birth date to our goal.

- We know that they likely won’t be on guard about sharing the date in the right context.

- We know that they’re our friend, and friends often ask personal questions and carry on conversations.

Based on this, our perlocutionary metrics might be:

- Level of distraction from our actual intent – if they believe we’re talking about astrology, for example, they might not connect the dots to a birthday party.

- Accuracy of the discussion – if they are being serious with us, they are more likely to give us the correct date rather than one composed as a joke or hyperbole.

We can test these assumptions in real time by asking them a leading question, such as – “What is your star sign?”.

Their response might be something akin to “Gemini, because this and this and so on.” if they care for astrology, or some amount of confusion or pushback if they do not. Noting that, we can amend our list of knowledge to include:

- Does/does not believe in astrology, a piece of information that might be useful if topics of spirituality, religion, mysticism or the supernatural ever come up.

Assuming they responded positively, the context is now primed for us to be subtle and ask about their birthday. We have established a context that satisfies our odds of aligning with our desired perlocutionary metrics and uses as many patterns and pieces of background knowledge as we have available. The success or failure of obtaining our desired information or objective then acts as a piece of validation towards our metrics.

Circling allllll the way back, it is exactly these types of guess and check instances that build up your pattern recognition – and once you have observed these patterns, you can begin to use them in choosing selective synonyms.

If we know that this person cares for astrology, we can give extra weighting to astrologically-connotated words, and potentially assume the same for spiritually-connotated terms.

This lets us build principles out for ourselves – the more information and patterns we can identify, the better our odds.

It’s not an easy process, and it’s certainly not foolproof. But you can only ever make progress forwards – information only ever helps make new connections and form new potential metrics, as long as you have the flexibility to discard metrics that don’t work and the patience to be wrong from time to time.

Conclusion

Language is an extremely complex beast, and intentionally choosing our speech to best suit our goals is both incredibly helpful and remarkably challenging. The imperfections of human knowledge and communication open up all manner of possibilities for misunderstanding and miscommunication – but with a calculated approach, we can get better at it.

Selective synonymy, the process of intentionally selecting words for their practical benefit to our intention behind our communications, is only a single tool in pragmatic forms of communication, and a robustly challenging skill to develop. Our best writers and speakers know this – the precision and intentionality of language is built upon it. With practice, anyone can improve the efficacy of their communication.

Stay informed

Receive updates on new research, book releases and insights into strategic communication and personal culture.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime. Your information is never shared.